D-Day, 6 June 1944, was one of the most significant operations of World War II, defining the start of the final phase of the war in Europe. After two to three years of preparations, the assault phase of ‘Operation Overlord’, code-named ‘Neptune’, lasted for little over three weeks and, by 30 June, had landed over 850,000 men on the invasion beachheads in Normandy, together with nearly 150,000 vehicles and 570,000 tons of supplies.

Much of the success of Operation Overlord was due to the creation of two artificial harbours, code named ‘Mulberry’, built in sections and towed across the Channel. The final decision to build the harbours was not taken until late August 1943 with design starting in October and construction in December allowing for a very short, six-month, construction period.

The artificial harbours were made up of three structures: outer breakwaters, pier heads and floating roadways that connected to the shoreline. For secrecy, each component was given a codeword. The breakwater comprised three elements: a floating outer line of connected hollow steel breakwaters (Bombardons); large rectangular concrete structures (called caissons) that were airtight enabling them to be sunk and re-floated (Phoenix); and an assembly of 60 obsolete vessels that would be scuttled to form a protective line of block ships (Gooseberries). The pier heads were made up of floating pontoons (Spuds) attached to legs that enabled the pier head to move up and down with the tide. The floating roadways (Whales), ten miles in length, were supported on floating pontoons (Beetles).

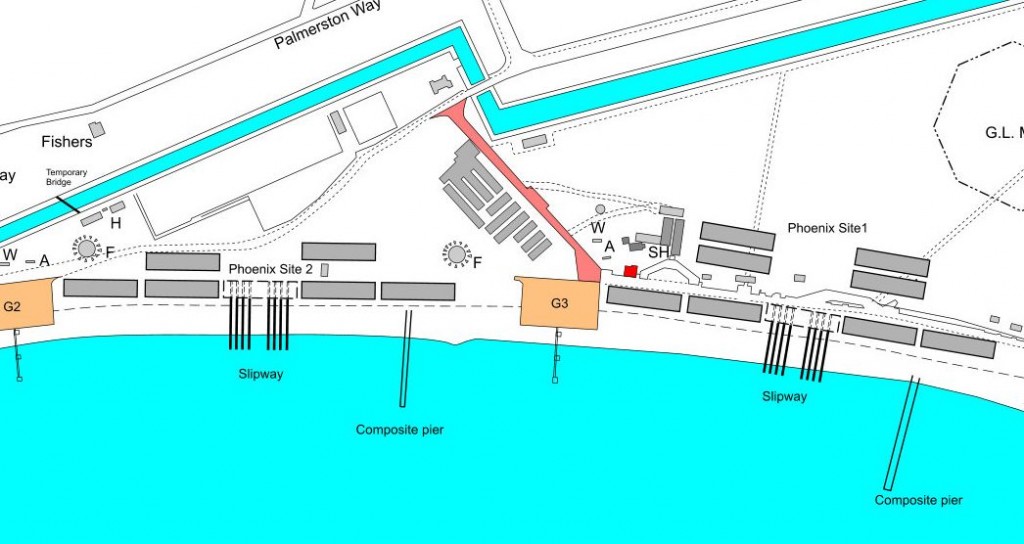

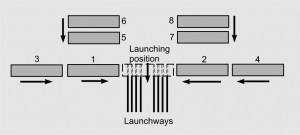

Fourteen of the type B2 caissons (Phoenix) were constructed at Stokes Bay at two construction sites ‘Phoenix 1’ and ‘Phoenix 2’, east and west of the present Stokes Bay Sailing Club building between the embarkation hards G2, G3 and G4. In the centre of each section was a launchway.

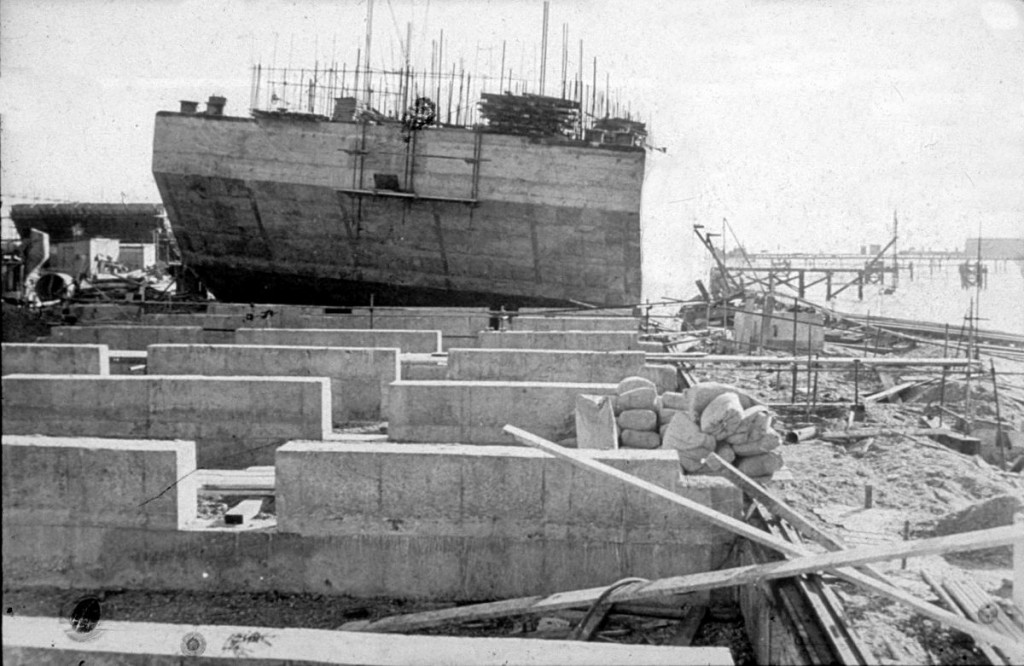

The B2 caissons, 203’6” long, 44’ wide and 35’ high weighing up to 6 tonnes, were made up of chambers that allowed them to be floated and scuttled as required. They were divided into 22 compartments in two rows of eleven separated by dividing concrete walls. There were no anti-aircraft guns fitted to the B2 caissons; they had sections at either end roofed over with concrete slabs. Each end was formed into a “swim end” to facilitate towing. In each of the compartments, valves for scuttling the floating caisson were fixed and the controls carried by special couplings and shafts which were extended to a gangway which ran inside the length of the caisson.

The caissons were partially constructed, launched sideways into the sea and moored to composite piers also constructed on site. A complicated system of winches was required to manoeuvre each caisson in sequence to its launchway. An aerial view taken in 1944 shows six units on the western site, south of the modern children’s play area, one on the launch slipway, four more on the shore waiting to be launched and one floating. One caisson caused a disaster: the launch “got out of control and collapsed the launchway”. Three men died and fifteen men were trapped beneath it putting back construction by one month whilst the caisson blocking the launchway was removed.

Once moored the caissons were completed to their full height, towed to one of two intermediate storage sites off Selsey and Dungeness, sunk to prevent them being seen from above and left to await D-Day when, partially submerged, they were towed by tugs out to their assigned beach where they were sunk to form breakwaters for the floating roadways and pierheads; even at high tide they would always create a barrier to waves entering the harbour.

Two harbours were planned; one on Gold beach; the other further west on Omaha beach. Assembly started on 9th June and by the 18th June the two arcs of caissons were in place. The following day a heavy storm wrecked the incomplete harbour on Omaha beach and severely damaged that at Gold beach. What could be salvaged from Omaha beach was transferred to Gold with the caissons remaining at Omaha still provided a sheltered anchorage for transhipment of supplies directly onto the beach. The surviving harbour at Gold continued in use into the winter of 1944 when the facilities at Antwerp were captured allowing for a new line of supply to the allied armies in Belgium and northern France.

The remnants of a Phoenix caisson can be seen in Langstone Harbour where it developed a crack and sank before deployment.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/mulberry-harbour-wreck

Remnants of “Beetles” are used as coastal protection in Southampton.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/mulberry-harbour-wreckage-southampton

Other remains of the Gold harbour are visible at Arromanche.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/mulberry-harbour-at-arromanches

A caisson that has fallen off the launchway. Three mooring dolphins for embarkation hard G4 in the background.

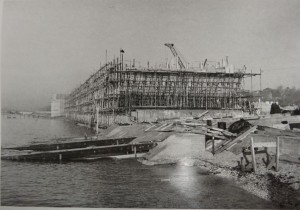

Phoenix construction site 1

A caisson under construction. In the foreground is the launchway

The west construction site showing the launchways and winches being constructed

In dry Summer months signs of the concrete foundations on which the ball carriages ran can be seen as lines in the grass to the east of the Stokes Bay Sailing Club compound. The Gosport Society D-Day Memorial marks the spot.